FLASHBACK: Exactly 50 years ago, how Adekunle Fajuyi gave up his life for Aguiyi-Ironsi

When next someone brands Nigerians a mass of ethnic zealots who are daily scheming how their ethnic group outpaces the other, you may not necessarily dispute their claims. But make sure to place it on record that there are a few shinning lights; and don’t forget to add that some of these limited but fine examples of ethnic unbias are as old as the country itself. Don’t bring down the curtain on your response, please, if you haven’t mentioned the events of July 29, 1966.

It was only six years after Independence, but it was already literally fashionable to be ethnocentric. Not exactly the kind of beginning that was fancied when the sonorous voice of Emmanuel Omatsola, legendary broadcast journalist, announced from Race Course: Nigeria is a free, sovereign nation.

Still, that was what it is.

FORESHADOWED CAPITULATION

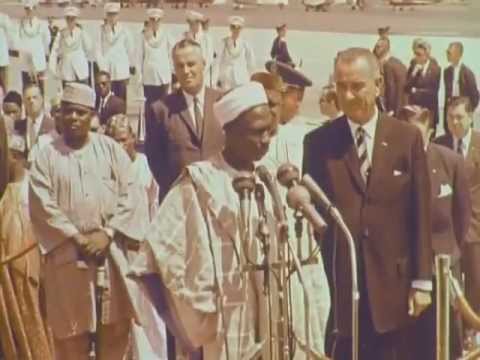

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, the prime minister who delivered Nigeria’s maiden Independence Day speech, was one of the most brilliant and learned Nigerians of his time. And although he succeeded in earning a reasonable degree of notoriety for championing northern interests — a splotch that nearly all leaders of other ethnic groups equally bore — he cut an influential and likable figure outside the country, illustrated by his frontline role in the founding of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) as well as in the negotiations for the resolution of the Congo Crisis of 1960 to 1964; in the condemnation of the South African Sharpeville Massacre of March 21, 1960 and in quelling the attempted expulsion of South Africa from the Commonwealth in 1961.

Sadly, for all his education and intelligence, the two-time prime minister misjudged the country’s foundations at Independence, which were anything but “well-built” as he thought. It was a blunder he never recovered from. Six years after delivering that fervent speech, Balewa paid with his life — alongside those of some others who championed the quest for Independence. With the benefit of hindsight, it was a death that was always coming. It was foreshadowed.

TUSSLE FOR SUPERIORITY

In the early 1950s when Nigeria’s century-long crave for independence began gathering steel, each region — northern, eastern, and western (as the country had been divided to by the Richards Constitution of 1946) — championed its own agenda. To every region, there was a political party to advance self-serving needs: the Northern Peoples Congress (NPC) for the north, the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) for the east, and Action Group for the west.

Writing a constitution suitable to the various interests proved a gruelling task. The north, the most populated of the three, considered autonomy from the other regions as well as a large representation in any federal legislature its birthright. In addition, it feared the fading of Islam — the dominant religion in the region — and as well worried over the economic might of the south.

The west itself craved autonomy, dreading the redistribution of its cocoa wealth to other regions. Only the broke east dithered, not exactly due to nationalist orientations but because of its survival needs, which it felt would best be served by a powerful central government and the redistribution of wealth.

The Lyttleton Constitution of 1954 attempted a compromise, creating a federation off the three ethnic regions, establishing a federal house of representatives and providing for the appointment of a premier for each region. Yes, it inched Nigeria closer to self-governance. But did it fix the festering regional rather than national drive for self-advancement? Certainly not.

Half-a-decade on, Nigeria was all but an independent nation. In December 1959, ethnicity-coloured federal parliamentary elections starring 10 political parties held — ethnicity-coloured because in addition to the three heavyweight parties (NPC, NCNC and AG), the names of the lightweights themselves easily gave their ethnocentric orientations out.

There was the Northern Elements Progressive Union, which, like the NPC, was formed to advocate northern interests; there was the Igala Union for Igala people; and similarly the Niger Delta Congress and the ostensibly chauvinistic Igbira Tribal Union.

As it was more of an inter-region contest than an inter-party affair, the most populated region — in this case, the north — stole the show. The NPC won 134 of the available 312 seats in the House, and then formed a coalition with five other parties and two independents to hold a summary 148 seats. At a distant second position with 89 seats was the NCN-led coalition, while the AG-led coalition had 75 seats.

INDEPENDENT BUT BELLIGERENT

From then until the mid-1960s, the country carried on with seething but bottled-up tension. The controversial censuses of 1962 and 1963 spawned fresh north-south acrimony, owing largely to allegations of population falsification. While that of 1962 was cancelled, a second attempt the following year was accepted, notwithstanding its official population figure of 55.6 million, which, compared to the modest effort a decade earlier, implied an improbable annual growth rate of 5.8 per cent. The polity was charged with suspicion, each region thinking the other manipulated the counting for local and regional political gains.

As the rumpus surrounding the census raged on, a separate turmoil was unfolding. In 1962, the Balewa government accused Obafemi Awolowo, idolised leader of the westerners — alongside other prominent leaders such as Olabisi Onabanjo, Anthony Enahoro, Lateef Jakande, Alfred Rewane, Ayo Adebanjo, Michael Omisade, Chike Obi, and Oladipo Maja — of treason. Awolowo’s British lawyer E. F. N. Gratien (QC) was denied entry into the country on the orders of the minister of internal affairs in a prelude to his eventual sentencing to 10 years in prison. Although Awolowo was eventually freed after Yakubu Gowon ascended the country’s reins, his supporters were already harbouring deep-seated animosity against the government.

With all these pent-up animosities across the regions, Nigeria was teetering on the brink of implosion by the time it became a Republic on October 1, 1963.

VIOLENCE FIRST

Post-independence, 1965 witnessed the maiden incident of large-scale politically-motivated killings in the country. But the stage had been set since the previous year, in the lead up to the country’s first election after independence.

On a side was the Nigerian National Alliance (NNA), comprising the Northern People’s Congress (NPC), Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), Midwest Democratic Front (MDF), Dynamic Party (DP), Niger Delta Congress (NDC), Lagos State United Front (LSUF), and the Republican Party (RP).

On the other side was the Unity Progressive Grand Alliance (UPGA), comprising the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC), Action group (AG), Northern Progressive Front (NPF), Kano People’s Party (KPP), Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU), United Middle Belt Congress, (UMBC), and the Zamfara Commoners Party (ZMC).

While the NNA was merely an effort of the NPC to help the north to federal might, it nevertheless appealed to voters outside region by presenting the benefits of associating with the party in power. UPGA, meanwhile, was NCNC’s footway to federal power, presenting itself as the alternative to northern dominance over other regions.

The standout feature of the time’s politicking was UPGA’s continued allegation of NNA’s plans to manipulate the election. For weeks, the election was postponed to resolve the shocking mismatch between the population of registered voters and the census figures. When it was finally to hold in December 1964, UPGA ordered a boycott that — in the end — was only partially effective.

In regions of effective boycott, elections held in March 1965. The NNA secured 198 of the 312 seats in the house of representatives (162 of those coming from NPC) while the NCNC-dominated UPGA lost out with 108 seats. When Samuel Akintola’s NNDP left NCNC in the dust in the November 1965 legislative elections in the Western Region, violence broke out. Within the next six months, about 2000 people died in violent clashes across the western region.

THEN A COUP

The chaos that followed the election tilted the country towards anarchy. The relationship between Balewa and Azikiwe deteriorated to such extent that it was thought that they weren’t on speaking terms. Both refused to meet to form a new government after the election, allowing opportunistic junior soldiers, led by Majors Emmanuel Ifeajuna and Kaduna Nzeogwu, to profit from the uncontrollable killings in the west by engineering a coup d’état in January 1966.

Balewa; Samuel Akintola, premier of western region; Ahmadu Bello, premier of northern region; and a number of senior military officers were murdered. The military officers and political leaders spared were mostly easterners, sending the signal that it was an eastern attack on the north.

Also, all but one of the arrowheads of the coup were easterners: Tim Onwuategwu, Don Okafor, a major, Chris Anuforo, Humphrey, all majors, as well as Emmanuel Nwobosi, Ben Gbulie and others who were all captains.

Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, a major-general and general officer commanding (GOC)), was the number-one beneficiary of the coup, stepping in to coerce the most senior political leaders alive to cede the country’s reins to him. And thus began what would eventually become decades of military rule.

AND A COUNTER-COUP

For a region that considered itself the natural heir to the country’s headship, the north was never going to accept the status quo. Aguiyi-Ironsi’s reign surely had to be temporary. Plus, the northern feeling of injustice was further aggravated by Aguiyi-Ironsi’s refusal to try plotters of the January putsch in line with military practice, despite acknowledging them as “rebels”.

July 29, 1966 was tragic. Murtala Mohammed, a lieutenant-colonel, led Theophilus Danjuma, a major, and Martin Adamu, a captain, to stage a reprisal coup.

Aguiyi-Ironsi, and head of state, was in Ibadan, Oyo state, as guest of Adekunle Fajuyi, a south-westerner and military governor of the western region. Considering the undercurrents of the coup, Fajuyi should have been the happiest man in the world to watch Aguiyi-Ironsi, an easterner die, but he refused to budge.

There are various accounts of the specifics of Fajuyi’s resistance: one is that he protested that his guest could not be killed unless he himself was first killed; another is that he fought to protect his guest and he died in the process. But what has always been clear is that the soldiers had not come for him; he constituted himself into an impediment and, for that, his life was taken. He was only 40 years old at the time (After the killing of hundreds of eastern military officers, 31-year-old Yakubu Gowon, a lieutenant-colonel and Aguiyi-Ironsi’s chief of staff, was installed as head of state.).

In the Nigeria of 2016, how many Yorubas can take a bullet for an Hausa? Or how many Igbos can so defend a Yoruba? We won’t find too many, obviously, but July 29 of every year offers us the assurance that while nationalists among us may be few and far between, they surely still exist.

Source: The Cable

Comments

Post a Comment